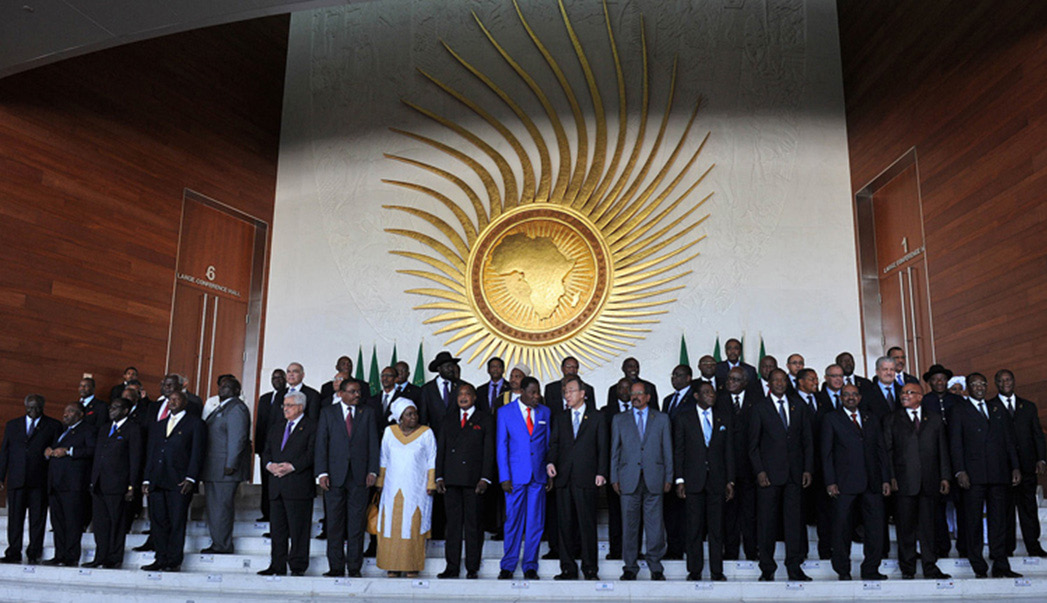

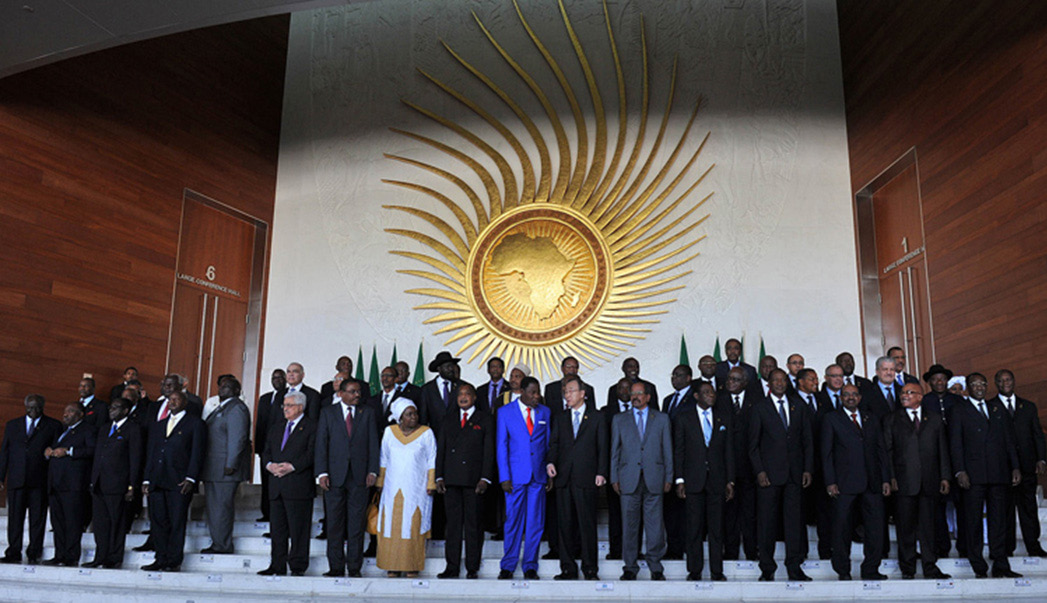

Long-time leaders won’t make way for new blood © GCIS

Instead of toppling autocrats across Africa, the AU’s lip service to democracy props them up

Critics have long argued that the African Union (AU) supports the authoritarian rule of many of the leaders of its member countries. They say it is little more than an old boys’ club for dictators — Paul Biya of Cameroon, Yahya Jammeh of Gambia (who has since conceded defeat in that country’s December 2016 presidential election) and Robert Mugabe of Zimbabwe, among others — who have been in power for decades. And that it offers these autocrats an apparently legitimate role on the international stage. Others add that the AU has allowed despots and counterfeit democrats to undermine genuine democratic reform in Africa whenever their grip on power is threatened.

At first glance, this may not be immediately apparent. Like many of the leaders of its member states, the AU is masterful at using the language and appearance of democracy, even as it helps to perpetuate authoritarian rule. Consider, for example, the AU’s most significant attempt — the Lomé Declaration, signed in July 2000 — to establish itself as a continent-wide force for democratisation and good governance.

The Lomé Declaration codified opposition to unconstitutional transfers of power as a binding principle of the AU. Specifically, any government that came to power though an unconstitutional transfer of power, such as a coup d’état, would be suspended from membership in the AU. For a region that has had more oustings than any other on the planet, this looked like a major step forward. Takeovers would not only be condemned rhetorically, they would also have tangible and predictable diplomatic consequences.

Moreover, the Lomé Declaration claimed that the AU would henceforth condemn, isolate, and suspend member state leaders who failed to relinquish power after losing a free and fair election. At the dawn of the new millennium, it seemed like a new dawn for democracy within the AU.

Yet, some unavoidable irony attended the signing of the declaration. Many of the signatory states had leaders who had come to power through coups. Faure Gnassingbé, the president of Togo, overthrew his father, who had also come to power in a coup. Many of the other member states were led by men who had rigged elections or had refused to hold them regularly. So the example set by those who signed the document was completely at odds with this new AU principle.

Unfortunately, the Lomé Declaration helped create an AU that is pragmatic with regard to policy — except for one overriding principle: a member country may only meddle in the affairs of another member state if it would accept the same intervention. If you’re a despot like Teodoro Obiang of Equatorial Guinea or José Eduardo Dos Santos of Angola, very few AU interventions seem acceptable. This helps explain not only the language of the AU’s faux commitment to genuine democracy but also its chequered implementation of its policies.

In 2001, when the AU was formalised, replacing the older Organisation of African Unity, some parts of the Lomé Declaration survived. Crucially, the provision barring unconstitutional transfers of power became Article 30 of the Constitutive Act, the founding document of the AU.

The AU’s experience with coups since adopting Article 30 is instructive. Military coups are uniformly anti-democratic in nature. Even when coups do prompt genuinely democratic elections, the damage done to the integrity of democratic institutions is substantial. Once a military has removed an elected leader from power, subsequent rulers must govern with an eye to avoiding the same fate as their predecessors.

The AU’s commitment to ending illegitimate transfers of power is admirable and an important signal that democratic legitimacy matters. It reminds us of the progress that the continent has made from its days of purely authoritarian one-party rule. Yet the organisation’s anti-coup norm is also a tool that allows entrenched despots to avoid the biggest risk to their power: being deposed by their own militaries. For most African despots, this is a far graver existential threat than rebellion, loss at the ballot box or Western intervention.

This is a crucial point. Article 30 apparently establishes a new norm demonstrating a laudable commitment to democratic reform. In reality, however, it represents an old-style power politics that allows authoritarian leaders to hide behind a veneer of legitimacy. In the long term, it will certainly be good to see fewer coups throughout Africa. But in the short term, Article 30 also serves the status quo. And in Africa, the status quo is despotism.

The anti-coup norm — like many of the AU’s rhetorical commitments — is flimsy. Madagascar was laudably suspended from the AU after a 2009 coup unseated Marc Ravalomanana, a democratically elected leader. But the AU’s subsequent engagement with Madagascar was never about reinstating him. Instead, the AU worked with the post-coup government in an awkward agreement that left Madagascar with a transitional government for nearly five years.

The main problem with the AU’s written commitment to democracy is that it is selective. Madagascar is no paragon of democracy, but should it have been suspended from the AU while the likes of Robert Mugabe or Teodoro Obiang were allowed seats at the table? This “democracy hypocrisy” is glaring. It undermines claims that the organisation is a force for genuine democratic change on the continent.

Today, Africa faces another critical challenge to democracy as presidents ignore restrictions —which they often penned — to their terms in office. The AU has been far too silent about this, and for a simple reason: many of the leaders of the AU’s most powerful states have long overstayed their welcome. If the AU is to be a force for genuine democratic change rather than a body that pays lip service to it, it needs to condemn such blatant violations of democratic principle. At present, however, it is a reluctant and half-hearted voice spouting platitudes and calls for restraint on all sides. The AU should change tack immediately, and institute strict penalties for leaders who do not abide by existing term limits.

Fourteen African heads of state have been in power for at least 15 years, and eight of them have been in power for more than a quarter of a century. All 14 of the longest-serving heads of state were in power when the Lomé Declaration was signed. Fifteen years later, they are the living embodiment of its failure.

The true test for the AU in the coming years will be whether it responds to the threat of coups in the same way it does to other equally damaging threats — rigged elections, violations of the rule of law and routine disregard for term limits — to democracy. For now, the AU’s claim to be a force for democracy rings hollow, as all too often it uses the language of democracy as a shield for despots.