African history: quo vadis?

Newly emerging African histories in the 1950s and 60s served as an antidote to the views of imperial and colonial historiography

African history has gone through many incarnations as an academic discipline. Most recently, there’s been a global turn in African historiography. This shift has been prompted by a greater awareness of the powerful forces of globalisation and the need to provide an African historical perspective on this phenomenon. This has helped to place the continent at the centre of global – and human – history. It’s important to explain the role of Africa in the world’s global past. This helps assert its position in the gradual making of global affairs. As an approach, it’s a radical departure from colonial views of Africa; it also complements the radical post-colonial histories that appeared from the 1950s and 1960s. And it may offer another framework for thinking through the curriculum reform and decolonisation debate that’s emerged in South African universities over the past few years. Afrocentric history emerged strongly during the 1950s and 1960s, in tandem with Africa’s emergence from colonial rule.

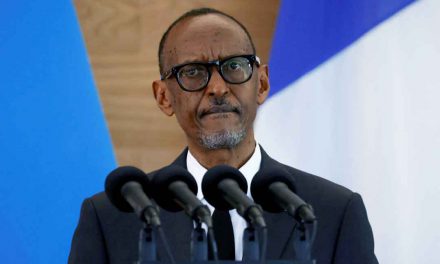

Newly emerging histories served as an antidote to the pernicious views of imperial and colonial historiography. These had dismissed Africa as a dark continent without history. But demonstrating that Africa has a long, complex history was only one step in an intellectual journey with many successes, frustrations and failures. The 20th century ended and a new one beckoned. The 21st century brought new sets of challenges. South Africa euphorically defeated apartheid, and the decolonisation project that started during the 1950s in west and north Africa was completed. These achievements were overshadowed by a horrific post-colonial genocide in Rwanda. Another genocide loomed in the Sudan. Coups, civil wars and human rights abuses stained the canvas on which a new Africa was gradually being painted. Africa’s woes were deepened by the emerging HIV/AIDS pandemic.

State driven, pro-poor policies and programmes founded during the early post-colonial period atrophied. This decay was driven by hegemonic global neo-liberal economic policies, and the study of history on the continent took a knock. Student numbers declined as post-colonial governments shifted their priorities. Global funding bodies focused their attention on applied social sciences and science, technology, engineering and mathematics disciplines. Nearly two decades into the new century there’s been another shift. The subject of history, alongside other humanities disciplines, is attracting growing attention aimed at averting their further decline. This can be explained in part by the subject’s own residual internal resilience and innovative research in newer areas of historical curiosity. There’s an emerging interest in history as a complementary discipline. Students of law, education, and political science are taking history as an additional option.

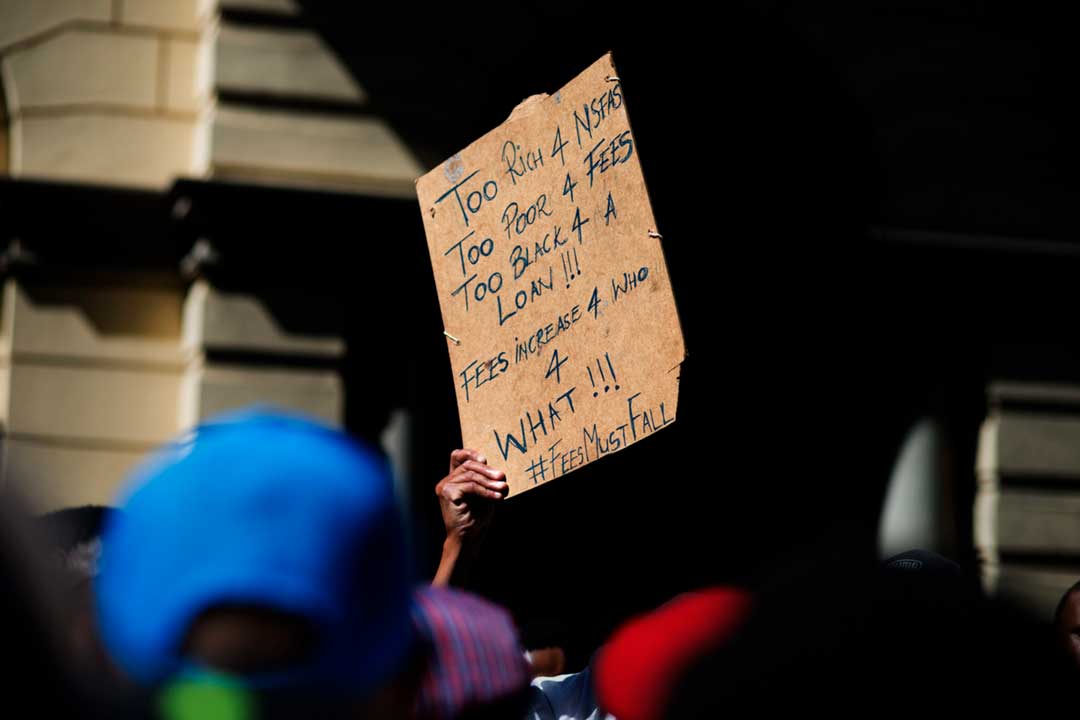

In South Africa in particular, history cannot be easily ignored, although it is contested. The country is still redefining itself and charting its new course after decades of apartheid and colonialism. However, a great deal of newer interest in history as a subject can be ascribed to university student movements. These movements have garnered greater public attention for ongoing debates about decoloniality and decolonised curricula. Decoloniality is a radical concept. Its main aim is to degrade the coloniality of knowledge. In South Africa, the decolonisation movement has been tied to bread and butter issues: tuition fees and access to higher education. Decoloniality affords both the language and the reason for seeking to dismantle what are regarded as western and colonial systems and structures of knowledge production and dissemination. But while decolonisation is riding a wave of academic interest, the histories of pre-colonial Africa are receding as an area of primary research focus.

A police officer looks on as Congress of South Africa Students (COSAS) demonstrate in support of the Fees Must Fall movement in Sandton, South Africa, in September 2016. Student protests spread around the country, with police firing rubber bullets at demonstrators on campuses in Johannesburg and Grahamstown as unrest over tuition fees roiled universities across the country. The wave of protests was triggered by a government announcement that universities would set their own fee increases. Photo: MUJAHID SAFODIEN / AFP

The histories of resistance to colonialism continue to resonate with current struggles for transformation and decolonisation. They have long been popular among historians in and of Africa. Indeed, several social and political movements have used decolonial interpretations of African history as their currency. However, questions continue to be asked about the kind of history curriculum that should be studied at university level at this moment. And what are the purposes of such curricula? Is an African history module a necessarily transformed one? What new conceptual and methodological tools should be deployed to describe and explain colonial encounters from a decolonial lens? What modes of ethics should inform such approaches? The challenges go beyond the conceptual aspects of decolonisation in the domain of African history.

There are historical structural formations, hierarchies and tendencies within academia that are rooted in coloniality. These make it a huge challenge to articulate newer forms of knowledge. At the same time, decoloniality should operate through other forms and frameworks. This will allow it to find application beyond its own self-defined frames. In addition, new approaches should challenge received wisdom and develop new kinds of curiosity. Newer curricula should, for instance, grapple with the fact that there is no single Africa. A unitary model of Africa is a colonial invention. Ordinary people’s identities form and evolve via multiple networks and knowledge forms. An Africa approached from its diverse histories and identities could help forge new, purposeful solidarities and futures.

A student holds a placard reading “Fees must fall” in Cape Town, October 2015, during nation-wide protests against fee hikes at tertiary education institutions. Similar protests were held at other universities around South Africa at the time. Many students said higher fees would further prevent poorer black youths from accessing a university education. Photo: RODGER BOSCH / AFP