Children from Kuma Garadayat (North Darfur) Image: UNAMID

Africa’s youth employment and education trends are worrying. Over the next few years much of the continent will be affected by two trends, namely continued high levels of unemployment and continuing high fertility rates.

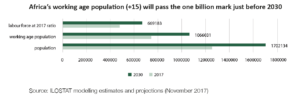

The latter, in particular, will lead to bulging youth populations in many countries around the continent. If not addressed adequately and quickly through appropriate policy actions the result will be disharmony – and possibly much worse – as well as even higher unemployment in the future. Africa’s working age population (those 15 years and older) will pass one billion people by 2030, according to United Nations (UN) statistics. That will be a 45% increase from 2105.

Of the 73 million jobs created in Africa between 2000 and 2008, only 22% were filled by youth, according to statistics from the International Labor Organization (ILO). The rate of unemployment among youth is currently estimated to be double that of adults in most African countries, according to the same study. The African Development Bank said in a 2015 report that creating new jobs and simply lowering the youth unemployment rate to that of adults would lead to an increase in Africa’s GDP of between 10% and 20%.

Of the 73 million jobs created in Africa between 2000 and 2008, only 22% were filled by youth, according to statistics from the International Labor Organization (ILO). The rate of unemployment among youth is currently estimated to be double that of adults in most African countries, according to the same study. The African Development Bank said in a 2015 report that creating new jobs and simply lowering the youth unemployment rate to that of adults would lead to an increase in Africa’s GDP of between 10% and 20%.

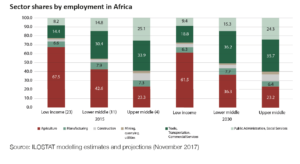

While the bank did not indicate a time frame, the increase would be significant even over a period of decades. More worrying, though, is that the structural composition of Africa’s labour force is not expected to shift significantly during this period. The African Centre for Economic Transformation (ACET), an economic policy institute based in Accra, Ghana, has argued that the lack of structural transformation of Africa’s economies could dampen opportunities for long-term economic growth.

A similar scenario may play out for employment in Africa. Unless structural changes emerge that are supported by robust and well-articulated policies, the labour force will neither respond to opportunities created by the Fourth Industrial Revolution (4IR; see the articles by ‘Gbenga Sesan, Dianna Games and Toby Shapshak in this edition of Africa in Fact), nor meet the needs of Africa’s youthful population.

For example, according to 2017 ILOSTAT data, Africa’s labour sector share in agriculture will decline from 67.5% in 2015 to 61.5% in 2030 for low-income countries. As another example, Africa’s labour sector share in trade and transport will decline from 25.1% in 2015 to 24.3% in 2030 for upper middle-income countries.

These incremental shifts will not allow Africa to capitalise on global trends in employment, which are now mainly driven by technology and innovation. Likewise, 2017 ILOSTAT survey data covering 25 African countries shows a very low labour sector share in manufacturing – only between 6% and 8% of total employment. That share is expected to decrease between 2015 and 2030, just when manufacturing could be driving employment generation.

The troubling labour trends are coupled with poor education outcomes. Last year, the McKinsey Global Institute (MGI) calculated that Africa needs to enroll 33 million young people in vocational and training education in secondary schools, whereas there were only four million enrolled in 2012. According to the 2018 World Development Report, Learning to Realise Education’s Promise, fewer than 7% of children in primary school are basically proficient in reading, while just 14% are basically proficient in mathematics.

The report notes a wide range of challenges, including children often suffering from illness or income deprivation. At the same time, teacher absenteeism is a significant challenge, as is the basic education of teachers in many countries. While many African countries certainly do face policy challenges when it comes to youth employment and skills agendas, it is also true that the types of jobs likely to be created over the coming decades may offer significant potential upsides.

For example, according to a working paper by James Bessen in 2016, it is estimated that computer use is associated with a 0.3% rise in overall national employment. Likewise, productivity growth (for example, from enhanced technology and innovation) in an industry tends to generate positive employment spillovers elsewhere in the economy, according to a 2017 study by David Autor and Anna Salomons. A one-unit increase in new automation leads to a 0.2% increase in the employment to population ratio, according to a 2017 article by Katja Mann and Lukas Putterman.

The new economy is also expanding opportunities. For example, online job sites and social networking platforms allow for a more diversified labour market participation, particularly for young women and disadvantaged groups. New jobs are being created that did not exist before, and market-entry space has been created for entrepreneurs – particularly regarding social enterprises. While there are concerns about job losses associated with automation and technology, we feel that the pace of change will likely allow Africa to see a net positive benefit over the medium term.

However, even with strong policy design and implementation, not all sectors will contribute equally to employment growth in Africa. It is likely that a few particular sectors will be the primary economic drivers. The ICT service sector has strong prospects in business process outsourcing (BPO), which is likely to bring more people into the labour markets, including women. Some studies indicate that one in four jobs in the United States have been – or could be – offshore in the future, according to a 2013 working paper by Alan S. Blinder and Alan B. Krueger. Interesting business models for medical services are developing that are increasingly taken offshore to countries such as India, China, the Philippines and South Africa. In India, the BPO industry already employs more than three million workers, 30% of who are women. In the Philippines, BPO employs 2.3% of all workers, according to the World Development Report 2016, Digital Dividends.

briefing entitled Ò1 + 4 = 16 Ð Targeting Poverty and Education for PeaceÓ (co-organized by the NGO Relations Youth Group and NGO Relations andAdvocacy, and Special Events Section, Outreach Division, Department of Public Information (DPI))

Agriculture also has significant potential to provide additional and higher-income jobs for the future, mostly due to high-end technology. Drones are being used for remote sensing, farm equipment is increasingly robotised to improve precision agriculture, and “telephone farming” is enabling city dwellers to farm remotely with access to irrigation, lighting, heating and weather-station data with smart-phone technology. According to a recent report by ACET, Agriculture Powering Africa’s Economic Transition, employment in Africa could be significantly boosted by the development of agricultural value chains, including agro-processing, input manufacturing and agricultural services. These sub-industries could open a host of productive employment opportunities in non-farm sectors.

Many of these jobs are likely to be attractive to Africa’s expanding population of educated youth, most of who do not think of “farming” as an appealing vocation. In the long term, bringing more young people into farming is essential for replacing the ageing traditional smallholders who are now the backbone of African agriculture.

While, according to the ILOSTAT data, the share of jobs in manufacturing will decline over the coming period, it will continue to be an important sector for employment. A few countries, such as Ethiopia, are starting to capitalise on the emerging opportunities in this sector. African manufacturing has traditionally lacked automation to boost productivity and competitiveness. Automation, of course, requires upskilling and improved infrastructure. The existing high-tech infrastructure could be adapted; indeed, in many cases it is only being expanded now, for example, with cellular networks and industrial electricity grids.

Moreover, a 2018 study from Karishma Banga and Dirk Willem te Velde of the Overseas Development Institute (ODI) indicates that African countries have a window of opportunity to move into somewhat less automated sectors, where technology installation has been slower. Automation varies greatly across sectors, with automotive and electronics sectors at the forefront while food processing and furniture production lag behind. This provides an opportunity for local and regional focused manufacturing.

Even as these industries become susceptible to automation, the 2018 report by ODI points out that Africa’s lower labour costs mean that African countries will have about a decade or longer to adjust before cost of robots fall enough to replace human labour.

This window should be used to build manufacturing capabilities and a continued focus on improvements in basic infrastructure such as a reliable power supply, telecommunications and roads – combined with a targeted approach to building industrial capabilities.

There are multiple approaches whereby African governments can immediately address the medium-term demand for skills for youth. Capitalising on the so-called “demographic dividend” represented by the high proportion of young people will not be automatic; it will require effective and ongoing policy implementation.

Firstly, Africa’s economies must create sufficient productive jobs, which requires strong and sustained growth. The Brookings Institution (2018) estimates the required economic growth to be in a range of between eight and nine percent. Industrial policies should favour labour intensity. Sectors such as agriculture and agro-processing, infrastructure, wholesale and retail trade, and tourism are particularly good candidates relative to their current growth rates and their economy-wide (infrastructure) or multi-sector (tourism) multiplier effects.

The transformation of the continent’s economies is crucial to ramp up growth. Clearly, governments will need to engage industry much more deeply and constructively than they have in the past. From a demand-side perspective, industry will need to be involved in improving skills quality and in enhancing access to technical and vocational training.

This can be facilitated by establishing skills councils and by industry participation in the quality assurance and assessment of learners. Government/industry collaboration on staff and student internships and training partnerships would be a critical element in this, based on national, regional and global best practice.

Likewise, governments will need to rapidly address regulatory and investment climates to expand job creation for youth. While making it easier to do business and improving the investment climate are important to industrial policy in particular, they are crucial regarding employment more generally.

This is because technologies are new and regulatory authorities, which tend to be conservative and understaffed, may not be nimble enough to develop needed regulations or may create stifling regulation based on poor understanding or unwarranted fears. Kenya, for example, has been at the forefront in creating a regulatory framework conducive to mobile banking, but fairly erratic in the development of drone regulations.

This is because technologies are new and regulatory authorities, which tend to be conservative and understaffed, may not be nimble enough to develop needed regulations or may create stifling regulation based on poor understanding or unwarranted fears. Kenya, for example, has been at the forefront in creating a regulatory framework conducive to mobile banking, but fairly erratic in the development of drone regulations.

At first, the country banned drones but then it introduced punitive drone regulations, charging exorbitant fees for their use. A recent ACET survey indicates a low level of awareness among policymakers of new technologies and their relevance to creating youth employment opportunities.

However, some governments are taking experimental approaches to help increase understanding. For example, South Africa’s Reserve Bank will allow experimentation with block-chain technology – a secure transaction ledger database that is shared by all parties participating in an established, distributed network of computers – in the banking sector because this will allow the institution to better understand them and thus to devise an appropriate regulatory regime.

Governments will not only need to expand and deepen skills development but focus on quality of skills for youth. Investment is needed in modern competencies for teachers and instructors, as well as updated teaching, learning and training facilities. While there has been some movement toward ICT-supported learning, it is not widely adopted or supported in most African nations. Enhanced cellular and broadband capabilities will enable African countries to leverage existing learning platforms.

But, of course, this will require adequate financing, which cannot be provided only by the public sector. African governments will need to establish dialogues and partnerships with the private sector to jointly finance quality skills development.

Finally, it will be necessary to improve access to – and perceptions of – technical and vocational education training (TVET) for and among Africa’s youth. Currently, perceptions of TVET among African policymakers and youth alike are that it is less prestigious, and less likely to result in improved socio-economic status, than tertiary academic education. TVET is therefore poorly funded, while facilities often do not cater to girls or people with disabilities. Governments need to invest more in understanding the demand for technical skills, and to make formal, concerted efforts to match skills to demand.

Presently, the opportunities are greater than the challenges as regards ensuring that Africa’s young people are provided with the skills that enable them to get jobs and build livelihoods. But all stakeholders will need to work together – and work quickly. In most instances, the required policy actions can be derived from global and regional best practices. That is not to say they are easy; there will be winners and losers. But it is imperative to manage the wins and losses now if we are to avoid losing an entire generation of young people, who are the future of Africa.