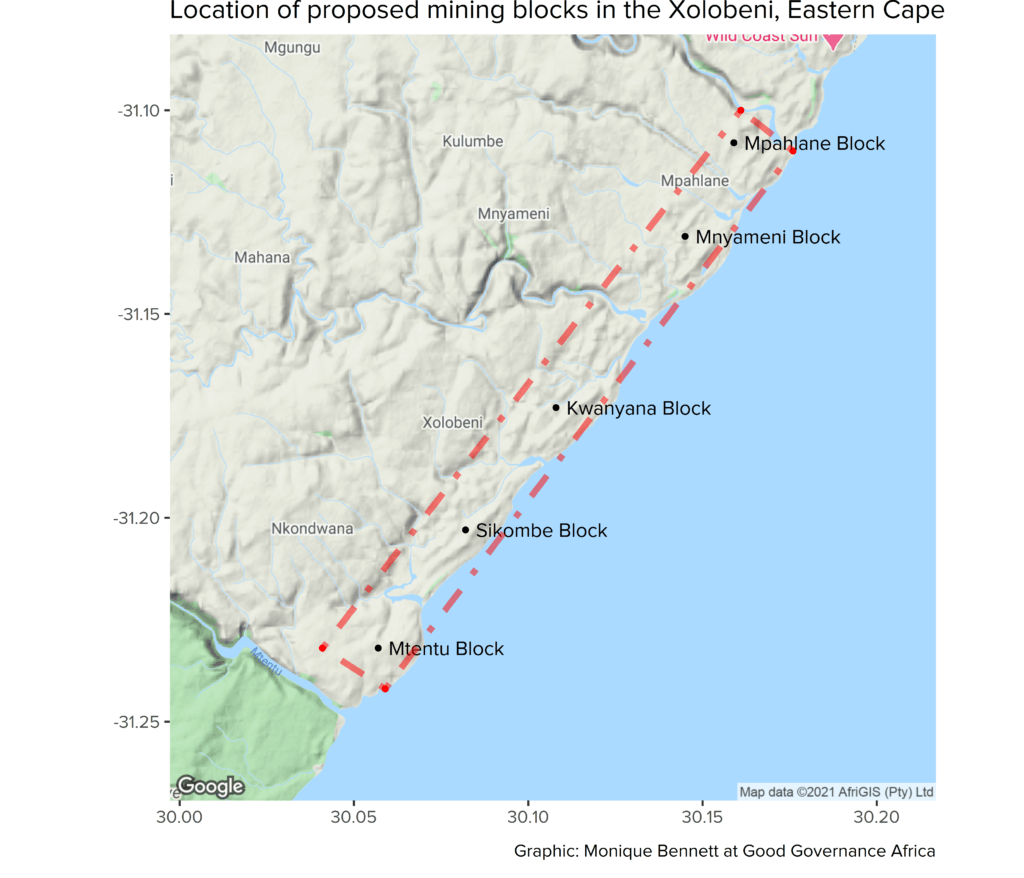

The Xolobeni community refers to a group of people from five coastal villages on South Africa’s Wild Coast who have been resisting plans to exploit world-class deposits of titanium-bearing minerals on a section of this coastline for almost fifteen years. Over this time, they have become organized (the Amadiba Crisis Committee leads local resistance to the mine), garnered support, and used public interest litigation under South Africa’s Constitution to advance their cause: The recognition of community vision and rights in relation to mining, sustainability, development and land.

Their cause: The recognition of community vision and rights in relation to mining, sustainability, development and land.

They have suffered violence in their community (between groups for and against the development of the region as a mining area and the construction of a major toll road) and personal loss: One of their leaders was assassinated in 2016, a second died after a short illness in November 2020, and a third received a death threat in the same month. And yet they continue to fight.

From the perspective of the proponents of the Xolobeni Mineral Sands project – various pockets of the State, some traditional authorities, the Australian ASX-Listed Mineral Resources Commodities Ltd (MRC), its subsidiary TEM and empowerment partner “Xolco” – the Xolobeni community is a massive obstacle to gaining a social licence to operate: A mining industry term of art denoting an informal social contract between a mining company and the communities surrounding its operations. The terms of that social contract are variously defined but include community support and co-operation in exchange for stakeholder recognition, infrastructure development, economic opportunity and jobs.

The case of the Xolobeni community, however, exposes the clay feet of the social licence model, which is the blank refusal of many powerful State and corporate actors to recognize any strong form of community rights over land and the right to determine particular local development trajectories.

From the perspective of the proponents of the Xolobeni Mineral Sands project, the Xolobeni community is a massive obstacle to gaining a social licence to operate.

A social licence to operate fits within a paradigm for mining-led development in resource rich developing countries that has its roots in colonial patterns of exploitation, production and consumption; the drive to liberalize, privatize and globalize in the 1980s and 90s; and the turn to sustainable development in the early 2000s. A key tenet of this paradigm, which I have elsewhere called the sustainable mineral development consensus, is that mining can catalyse sustainable development that alleviates poverty and promotes economic growth if resource rich countries take on board a package of economic and institutional reforms: Instituting the State as the central custodian of mineral rights, protecting investor rights through security of mineral tenure, charging profit – rather than production-based taxes – and “managing” environmental impacts, amongst others. Under this paradigm, communities are stakeholders and interlocutors. They are not protagonists and they are certainly not rights-bearers.

But despite implementing these reforms, Richard Auty’s “resource curse” still dogs the economic performance and development outcomes of some countries with a significant natural resource endowment. Some, but not all. As a recent review of the resource curse theory points out, the presence of a natural resource sector does not necessarily translate into worse development outcomes. Much turns on the type of States and political institutions in which resource-abundant economies develop, with political and economic inclusion being key.

A social licence to operate fits within a paradigm for mining-led development in resource rich developing countries that has its roots in colonial patterns of exploitation, production and consumption.

The question is: Would greater recognition of community rights ground a social licence to operate that could reverse the resource curse?

In South Africa, public interest litigation has led to growing recognition of community rights in a mining context. In the 2010 case of Bengwenyama Minerals (Pty) Ltd v Genorah Resources, the Constitutional Court expounded the meaning of “consultation” between mining companies and communities, holding that landowners must be informed in sufficient detail of prospecting or mining operations that will take place on their land, and that there must be a good faith attempt to reach agreement with landowners on the impact of extractive operations. In the more recent case of Maledu & others v Itereleng Bakgatla Mineral Resources (Pty) Ltd the Constitutional Court held that the granting of a mining right under the Mineral and Petroleum Resources Development Act, 2002 did not nullify communities’ informal land rights under the Interim Protection of Informal Land Rights Act (IPILRA), 1996 and that the two statutes must be read in a manner that permits each to serve their underlying purpose.

Further compounding the problem is that the former ‘homelands’ (like the Transkei) are characterised by insecure communal land tenure, a problem that remains unresolved despite constitutional provision for greater security. The upshot of this injustice is that traditional leaders tend to hold disproportionate levels of power and may be susceptible to striking bargains with mining companies and state departments that prove destructive to communities and their environments.

In South Africa, public interest litigation has led to growing recognition of community rights in a mining context.

The Xolobeni community has been at the forefront of the fight to secure judicial recognition of community rights. In the 2019 case of Baleni & others v Minister of Mineral Resources the High Court decided that community members could not be deprived of their land rights under IPILRA without their full, prior and informed consent (although this judgment is being appealed). And in a judgment handed down in September 2020, the High Court agreed that communities had a right of access to the information in a prospecting or mining right application without needing to submit a request under the Promotion of Access to Information Act.

And in February 2021, Judge Goliath of the Western Cape High Court handed environmental activists a momentous legal victory when she recognized that MRC’s claim for defamatory damages against a few activists for statements they had made criticizing the company’s operations in the Eastern and Western Cape matched the “DNA” of a SLAPP suit (Strategic Litigation Against Public Participation). Speaking out against any attempt to “weaponise” the South African legal system she underlined the essential role that freedom of expression, robust public debate, and the ability to participate in those debates without fear, played in a democratic society and recognized a “SLAPP suit defence” in South African law.

In a judgment handed down in September 2020, the High Court agreed that communities had a right of access to the information in a prospecting or mining right application without needing to submit a request under the Promotion of Access to Information Act.

Taken together, these individual court victories for community and activist rights are establishing the bedrock for a more authentic social licence to operate in South Africa. Over the long term, greater recognition of community rights in a mining context could strengthen the inclusivity of political and economic institutions necessary to start addressing the tragic legacy of the resource curse, not only in South Africa but throughout the continent.

Tracy-Lynn Field is a full professor at the School of Law at the University of the Witwatersrand (Wits), and advocate of the High Court of South Africa. Professor Field’s work focuses on the law and governance of extractives-based development, climate change, water, and Earth stewardship. She’s also the author of ‘State Governance of Mining, Development and Sustainability’, and has chaired the board of the Centre for Environmental Rights since 2017, actively supporting civil society organisations to secure climate-resilient development for Africa.